Open Wednesday to Saturday, 12 p.m. to 6 p.m.

Image: Name, Title, Description

Brought in Bondage: Black Enslavement in Upper Canada

Developed In Partnership With The Ontario Black History Society

People Of African Descent Have A Unique Experience Of Arrival To The Early Toronto. The First Africans In The Town Of York Arrived Through Forced Migration As The Enslaved Property Of The Military And Government Elite White Loyalists Who Relocated To The Town. White Loyalists Enslaved Black Men, Women, And Children To Exploit Their Labour For The Purpose Of Increasing Personal Wealth And To Support The Development Of The New Colonies With The Use Of A Free Labour Force.

Enslaved Africans Were Legally Chattel Property And Did Not Have Any Rights Or Freedoms. They Were Considered To Be Property And Not Persons.

Click ‘Learn More’ In The Map Below To Begin Our Tour

This self-guided walking tour was developed in partnership with the Ontario Black History Society.

Explore More

There are vibrant hues hiding in unexpected places around the

A Taste of Beekeeping in Toronto

Learn about urban beekeeping, the city's honeybee population, and partake

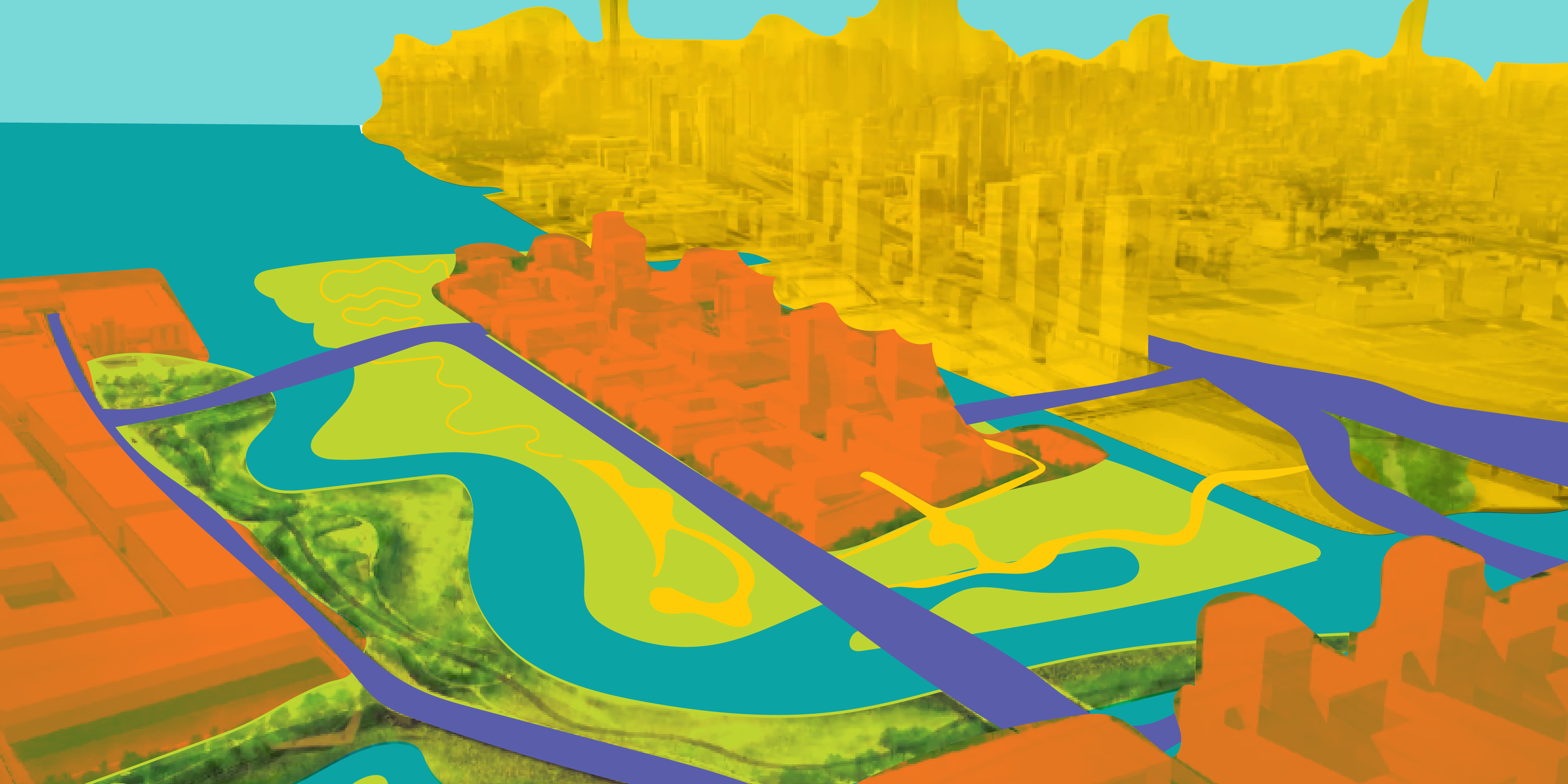

Conversations on Toronto’s Don River Redevelopment

What is the future of Toronto's iconic Don River?

Mushrooming, Foraging & Native Pollinator Gardens in Toronto

Uncover how Toronto's unique world of plants and mushrooms is

Untold Stories of Toronto’s Waterfront: A Talk with Author M. Jane Fairburn

A unique talk that invites you to rediscover the past,

Urban Forest Bathing: A Guided Meditation Session

Come downtown to discover nature blooming through the concrete! Join

Share this Article

Explore More

Content

Urban Colour & Natural Dyes Workshop

There are vibrant hues hiding in unexpected places around the city! Learn the art of creating dyes with the Contemporary Textile Studio Co-Op

A Taste of Beekeeping in Toronto

Learn about urban beekeeping, the city's honeybee population, and partake in a honey tasting!

Conversations on Toronto’s Don River Redevelopment

What is the future of Toronto's iconic Don River?

Mushrooming, Foraging & Native Pollinator Gardens in Toronto

Uncover how Toronto's unique world of plants and mushrooms is right at your fingertips

Untold Stories of Toronto’s Waterfront: A Talk with Author M. Jane Fairburn

A unique talk that invites you to rediscover the past, present and future of life along Toronto's waterfront.

Urban Forest Bathing: A Guided Meditation Session

Come downtown to discover nature blooming through the concrete! Join us for an urban forest bathing experience.

Myseum of Toronto Changes Its Name to ‘Museum of Toronto’

Myseum of Toronto Changes Its Name to ‘Museum of Toronto’ The Museum of Toronto is Toronto’s City Museum Toronto, ON (April 2, 2024) Today, Myseum of Toronto announced it will

Protected: TGW Preview

There is no excerpt because this is a protected post.

Press Releases and Media

Press Releases and Media Museum of Toronto Recent Press Releases Find Usin the News

PAT Market: A Torontonian Grocer and Koreatown Staple

As a landmark independent grocery store, PAT continues to bring Torontonians together over a love for food and a commitment to serve their local community.