Open Wednesday to Saturday, 12 p.m. to 6 p.m.

The Birth of Medicare in Canada

Image: T.C. Douglas, NDP Leader, 1969, Toronto Public Library Archives

Learn about the compelling origins of Canada's healthcare system.

Previous slide

Next slide

Credit: Toronto Star Photograph Archive, Courtesy of Toronto Public Library. Library and Archives Canada.

Douglas’s prediction was almost on target. By 1971, the groundwork he and his government had laid in Saskatchewan had spread across the country, as a series of federal and provincial laws provided Canadians with public health coverage, regardless of income.

“Douglas’s achievement in introducing medicare in Saskatchewan represented a deep conceptual shift that radically altered the provision of health care in Canada,” Vincent Lam observed in his 2011 biography of Douglas. “He convinced a nation that in a civilized society, health care should be considered essential to individual and social well-being, and viewed both as a public right and a collective obligation.” Douglas’s Medicare legacy helped earn him the title “The Greatest Canadian of All Time” during a 2004 CBC competition.

Following Confederation in 1867, health care was considered a provincial responsibility. Ideas for public health coverage were discussed seriously following the aftermath of the First World War. A health insurance act passed in Alberta in 1935, but never implemented due to a change in government soon after. A law passed in British Columbia the following year died due to intense opposition from doctors and insurance companies, as well as failure to secure additional federal funding.

“The Government of Saskatchewan is convinced that the time has arrived when we can establish a prepaid medical care plan in our march toward a comprehensive health insurance program that will cover all our people, and will ensure a high standard of medical care to every citizen of Saskatchewan…If we can do this — then I would like to hazard a prophecy that, before 1970, almost every other province in Canada will have followed the lead of Saskatchewan, and we shall have a national health insurance program from the Atlantic to the Pacific.”

— Tommy Douglas, 1959.

Previous slide

Next slide

In Saskatchewan, health care was a top priority for the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF, the ancestor of the NDP) after they gained power under Douglas in 1944. He could trace his interest to frequent childhood hospitalizations for osteomyelitis (bone infection). When doctors wanted to amputate a leg, orthopedic surgeon J.R. Smith agreed to work on it for free as long as his medical students could watch. “I think it was out of this experience,” Douglas reflected years later, “that I came to believe that health services ought not to have a price tag on them, and that people should be able to get whatever health services they required irrespective of their individual capacity to pay.”

After introducing programs providing relief for people ranging from the blind to single mothers, the CCF passed the Hospital Insurance Act. When it went into effect in 1947, the act guaranteed government-funded hospital care for Saskatchewan residents. Douglas reassured doctors and hospitals that the government was taking over paying the bills, not the administration or ownership of facilities. By 1954, 810,000 people were covered by this plan, and the province had the most hospital beds per capita in Canada.

Other provinces developed their own hospital care plans. In Alberta, a subsidy was introduced in 1950 for those who couldn’t pay market insurance rates, while leaving the option of private plans for everyone else. Ontario proceeded slowly, as Premier Leslie Frost waited for the hospital system to expand enough to handle the province’s population growth. He pushed to add health insurance to the agenda during federal-provincial meetings in 1955, but faced opposition from eastern provinces and Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent. Frost may have also been irritated when two of his individual health policies were cancelled when he turned 60 that year.

Further discussion resulted in the federal passage of the Hospital Insurance and Diagnostic Services Act in 1957, which offered to pay around half the cost of provincially-run hospital insurance plans. By 1961, all provinces had signed on.

Feeling that Saskatchewan’s finances could support a fuller medicare program, the CCF made it the focus of the 1960 provincial election campaign. They were opposed by the Saskatchewan College of Physicians and Surgeons (CPS), who believed medicare would be expensive and harm the independence of doctors. Some of their views came from doctors who had recently emigrated from Great Britain, disliked that country’s National Health Service, and feared a similar program. Backed by the American Medical Association and Canadian Medical Association, the CPS’s propaganda campaign painted a dark picture of doctors fleeing the province, leaving residents with poor health care provided by “the garbage of Europe.” The public rejected the fearmongering, giving the CCF their fifth straight victory.

Shortly after the government introduced the Saskatchewan Medical Care Insurance Act in October 1961, Douglas resigned as premier to become the NDP’s first federal leader. His successor, Woodrow Lloyd, continued to negotiate with the doctors, but their stubborn opposition caused talks to fall apart. When the act took effect on July 1, 1962, Saskatchewan’s doctors withdrew their services except for some emergency care. They refused to continue negotiations unless the government immediately repealed the act. Over the next three weeks, public opinion went from divided to supporting the government’s stance as the CPS and their allies unconvincingly attacked medicare. A few hotheads predicted the situation might become violent.

While the press within Saskatchewan supported the doctors, everywhere else their actions were criticized, primarily for refusing to negotiate in good faith. “Most of the western world has long since adopted the principle of insurance” a Financial Post editorial observed. “Do the Saskatchewan strike leaders think they can change the thinking, the practices and the attitudes of hundreds of millions of people?”

As the strike continued, some doctors decided to prioritize their patients and returned to work. A mediator was brought in and, after 23 days, the strike ended. When the CCF/NDP was defeated in the 1964 provincial election, its successors maintained medicare.

Over the next few years, the other provinces developed their own plans, primarily based around a mixture of public support for the poor, private plans with regulated rates for everyone else. Following the recommendations of the Royal Commission on Health Services, the federal government passed the Medical Care Act in 1966. It outlined cost-sharing and required provincial plans to be universal and publicly administered before transfer payments were made. When this act when into effect in July 1968, only British Columbia and Saskatchewan were eligible for federal contributions. Despite their reservations, the rest of the provinces followed, ending with New Brunswick in January 1971. In Ontario, where much of the private insurance industry was based, Premier John Robarts called medicare “one of the greatest political frauds ever perpetrated on this country.” By October 1969 Ontario had joined in, introducing the Ontario Health Services Insurance Plan, which evolved into today’s OHIP. Further reforms occurred with the passage of the Canada Health Act in 1984, which included penalties for user fees and extra billing.

Explore Further

Extraordinary Canadians: Tommy Douglas

By Vincent Lam

256 Pages. Penguin Random House, 2011.

Health Care in Canada: A Citizen’s Guide to Policy and Politics

By Katherine Fierlbeck

384 pages. University of Toronto Press, 2011.

Making Medicare: The History of Health Care in Canada, 1914-2007

Canadian Museum of History

Explore More

There are vibrant hues hiding in unexpected places around the

A Taste of Beekeeping in Toronto

Learn about urban beekeeping, the city's honeybee population, and partake

Share this Article

Explore More

Content

Urban Colour & Natural Dyes Workshop

There are vibrant hues hiding in unexpected places around the city! Learn the art of creating dyes with the Contemporary Textile Studio Co-Op

A Taste of Beekeeping in Toronto

Learn about urban beekeeping, the city's honeybee population, and partake in a honey tasting!

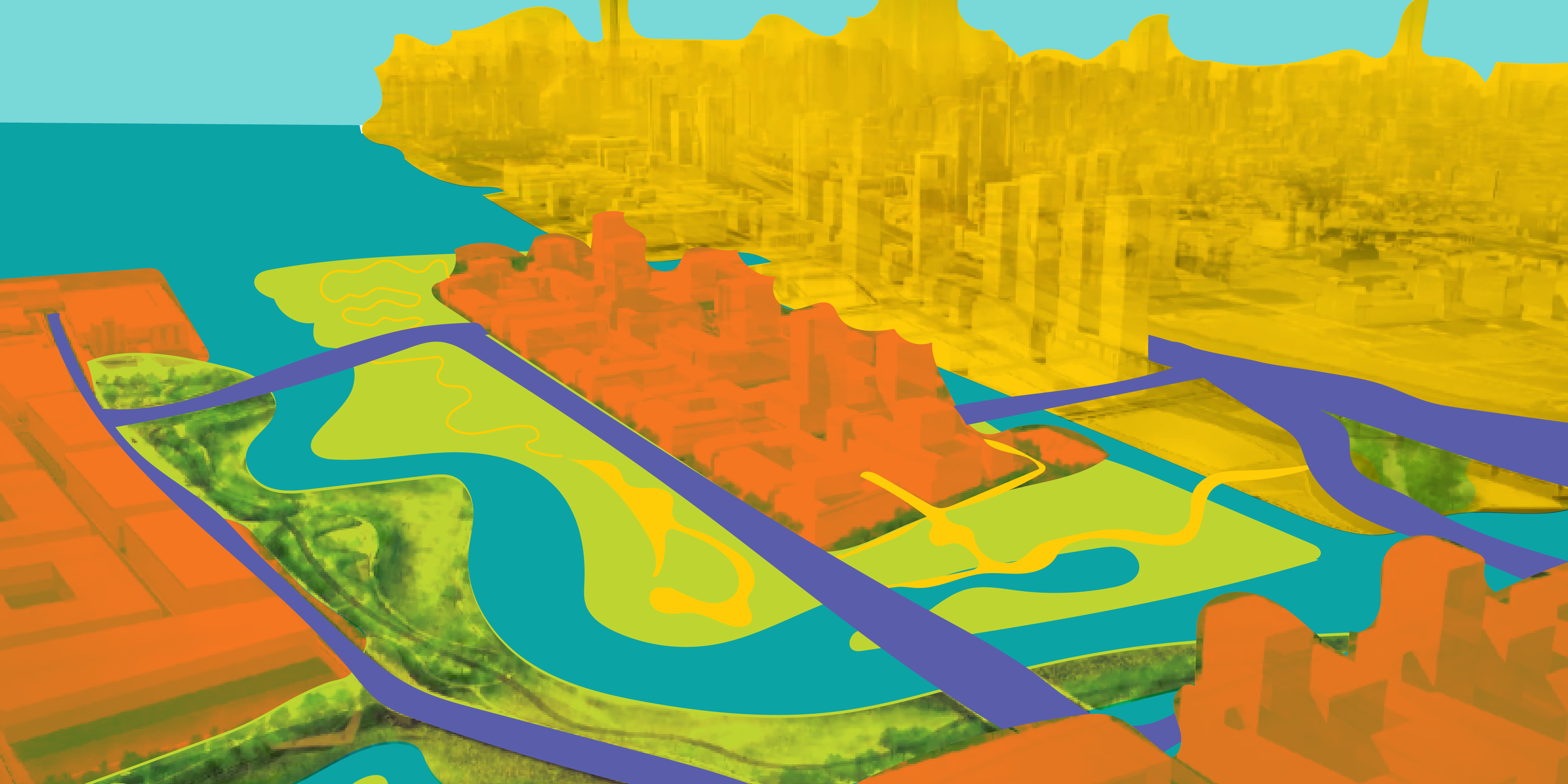

Conversations on Toronto’s Don River Redevelopment

What is the future of Toronto's iconic Don River?

Mushrooming, Foraging & Native Pollinator Gardens in Toronto

Uncover how Toronto's unique world of plants and mushrooms is right at your fingertips

Untold Stories of Toronto’s Waterfront: A Talk with Author M. Jane Fairburn

A unique talk that invites you to rediscover the past, present and future of life along Toronto's waterfront.

Urban Forest Bathing: A Guided Meditation Session

Come downtown to discover nature blooming through the concrete! Join us for an urban forest bathing experience.

Myseum of Toronto Changes Its Name to ‘Museum of Toronto’

Myseum of Toronto Changes Its Name to ‘Museum of Toronto’ The Museum of Toronto is Toronto’s City Museum Toronto, ON (April 2, 2024) Today, Myseum of Toronto announced it will

Protected: TGW Preview

There is no excerpt because this is a protected post.

Press Releases and Media

Press Releases and Media Museum of Toronto Recent Press Releases Find Usin the News

PAT Market: A Torontonian Grocer and Koreatown Staple

As a landmark independent grocery store, PAT continues to bring Torontonians together over a love for food and a commitment to serve their local community.